The Little Key of Solomon

Various English Manuscripts, 17th C

Sloane 3825 | Sloane 2731 | Sloane 3648 | Harley 6483

The Lesser Key of Solomon, also known as Clavicula Salomonis Regis or Lemegeton, is a grimoire spuriously attributed to King Solomon on the ceremonial art of commanding good and evil spirits. It was compiled in the mid-17th century, mostly from materials that were written two centuries earlier. It is divided into five books: Ars Goetia, Ars Theurgia-Goetia, Ars Paulina, Ars Almadel, Ars Notoria

1. Ars Goetia

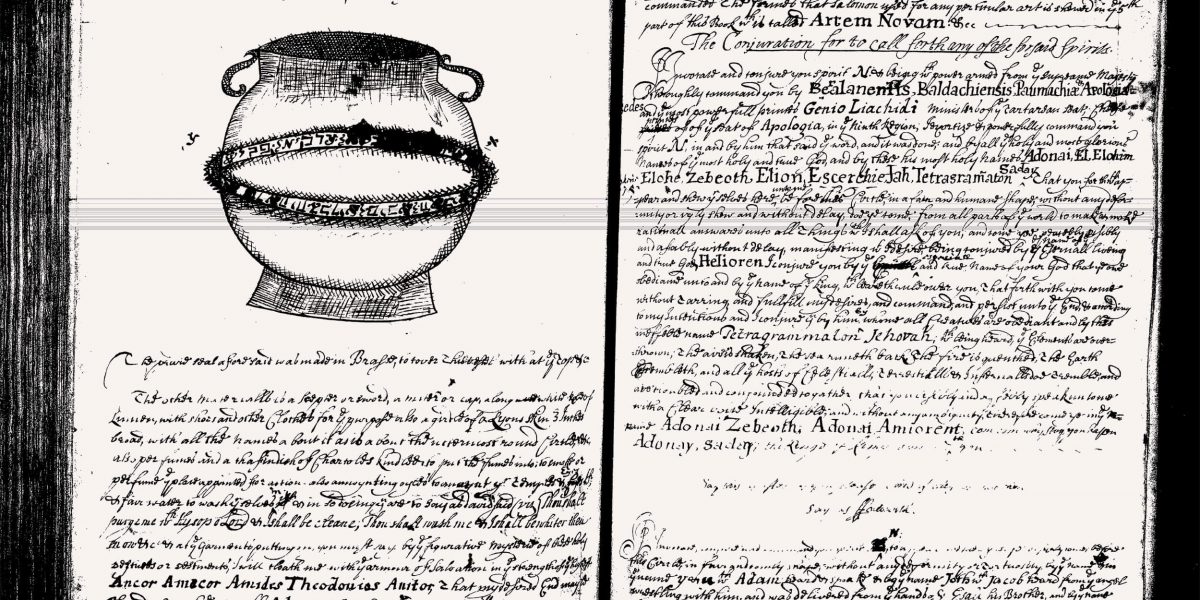

The first book, Goetia, is a grimoire containing descriptions of the seventy-two demons that King Solomon is said to have evoked and confined in a bronze vessel sealed by magic symbols, and that he obliged to work for him. The text assigns a rank and a title of nobility to each member of the infernal hierarchy, and gives the demons “signs they have to pay allegiance to”, or seals.

The most obvious source for the Ars Goetia is Johann Wier’s Pseudomonarchia daemonum published in 1563 with his De Praestigiis Daemonum although he claimed his text to based upon an even earlier work, Liber officiorum spirituum, seu Liber dictus Empto. Salomonis, de principibus & regibus dæmoniorum (“Book of the offices of spirits, or the book called Empto. Salomonis concerning the princes and kings of the demons”). This exact manuscript is yet to located however another 15/16th century French work, Livre des Esperitz (Book of Spirits) is clearly related. None of these manuscripts include seals for the demons and they are invoked by a simple conjuration as opposed to the elaborate ritual found in the Lemegeton. These features are therefore a later addition. Below are the 72 demons of the Ars Goetia.

| King Bael | Count/President Glasya-Labolas | Duke Crocell |

| Duke Agares | Duke Buné | Knight Furcas |

| Prince Vassago | Marquis/Count Ronové | King Balam |

| Marquis Samigina | Duke Berith | Duke Alloces |

| President Marbas | Duke Astaroth | President Caim |

| Duke Valefor | Marquis Forneus | Duke/Count Murmur |

| Marquis Amon | President Foras | Prince Orobas |

| Duke Barbatos | King Asmoday | Duke Gremory |

| King Paimon | Prince/President Gäap | President Ose |

| President Buer | Count Furfur | President Amy |

| Duke Gusion | Marquis Marchosias | Marquis Orias |

| Prince Sitri | Prince Stolas | Duke Vapula |

| King Beleth | Marquis Phenex | King/President Zagan |

| Marquis Leraje | Count Halphas | President Valac |

| Duke Eligos | President Malphas | Marquis Andras |

| Duke Zepar | Count Räum | Duke Flauros |

| Count/President Botis | Duke Focalor | Marquis Andrealphus |

| Duke Bathin | Duke Vepar | Marquis Kimaris |

| Duke Sallos | Marquis Sabnock | Duke Amdusias |

| King Purson | Marquis Shax | King Belial |

| Count/President Marax | King/Count Viné | Marquis Decarabia |

| Count/Prince Ipos | Count Bifrons | Prince Seere |

| Duke Aim | Duke Vual | Duke Dantalion |

| Marquis Naberius | President Haagenti | Count Andromalius |

2. Theurgia-Goetia

The Ars Theurgia-Goetia mostly derives from Trithemius’s Steganographia, though the seals and order for the spirits are different. Rituals not found in Steganographia were added and Trithemius’ cryptographic conjurations removed.

Both the Steganographia and the Theurgia-Goetia are concerned with spirits which relate to the points of a compass. In effect, it supplements the Goetia which is quite vague about where to position the Triangle of the Art outside the circle. Some manuscripts of the Theurgia-Goetia supply a full blown Spirit Compass showing all 32 possible directions from which a King, Prince, or Duke can be expected to arrive. One original manuscript of the Steganographia contains an illustration with 16 segments but, for reasons unknown, the printed editions are incomplete including an illustration with just 3 of the 16 Dukes filled in. Below are the versions of The Spirit Compass Rose from the Steganographia (left) and Theurgia-Goetia (right).

Although the Steganographia lacks the copious spirit seals in the Theurgia-Goetia, those seals that can be found in Steganographia match exactly. Below are the seals dealing with the eleventh spirit, Usiel, and his subordinates, from right to left: Adan, Ansoel, Magni and Abariel:

Steganographia, I. chapter xi.

Lemegeton: Theurgia-Goetia

3. Ars Paulina

Derived from book three of Trithemius’s Steganographia and from portions of the Heptameron, but purportedly delivered by Paul the Apostle instead of the Angel Raziel as claimed by Trithemius. Elements from The Magical Calendar, the seals for each sign of the Zodiac repurposed from Robert Turner’s 1656 English translation of Paracelsus’s Archidoxes of Magic, and repeated mentions of guns and the year 1641 indicate that this portion was written in the later half of the 17th century.

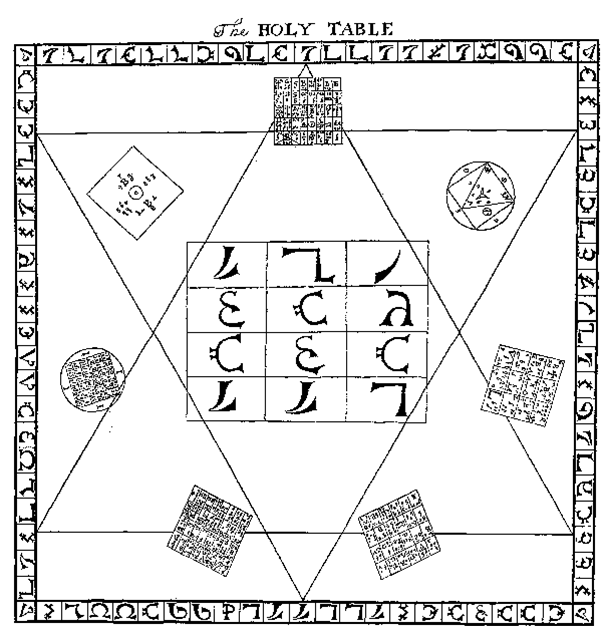

The Ars Paulina is divided into two books, the first detailing twenty-four angels aligned with the twenty-four hours of the day, the second (derived more from the Heptameron) detailing the 360 spirits of the degrees of the zodiac. The book instructs the practitioner on how to fashion the “Table of Practice”, an alter upon which a crystal or glass receptacle should be centrally placed. Around it are placed six seals [from Paracelsus’s Archidoxes of Magic] each representing a planet. John Dee’s “Tabula Sancta” (or Holy Table) serves the same purpose. Below are the both the “Table of Practice” (left) and Dee’s “Holy Table” (right).

4. Ars Almadel

The Ars Almadel instructs the magician on how to create a portable alter for communicating with angels via scrying. It consists of a square plate of wax engraved with magical names and characters, which rests upon four candles constructed with special feet for suspending the plate in the air. The plate has holes in the corners, and incense is burned beneath it so that the smoke flows through the holes. The spirit is expected to appear either in the smoke that rises through the holes or in a crystal that sits in the center of the alter.

The practice of gazing into smooth surfaces to produce visions and communicate with spirits began with the Muslims and the ancient Hebrews. In Muslim lands this tradition is called darb al’mandal, or drawing the circle, which is most likely where the word, “Almadel” is derived. The Hebrew equivalent is called Sarei shemen, “the princes of the oil”. They borrowed the practice from Babylonians while in captivity which in turn was handed down from the Sumerians. In all these techniques, the diviner instructs a subject [or the diviner alone] to gaze into a smooth, shiny surface where the princes, most commonly conceived as demons or angels, were expected to appear. The use of incantations and magical characters are also consistent with these techniques. Where the Almadel requires the writing of magical names on wax, the Hebrews and Muslims wrote them on bowls, cups, mirrors, or even the hands and forehead of a seer.

Both Trithemius and Weyer reference this work in their writings. A 15th-century copy is attested to by Robert H.Turner, and Hebrew copies were discovered in the 20th century.

5. Ars Notoria

The Ars Notoria (or Notary Art) is not only the oldest portion of the Lemegeton but one of the oldest grimoires in the Solomonic tradition of magic. The work has been pseudepigraphically attributed to prominent figures such as Euclid of Thebes, Apollonius of Tyana, and King Solomon, who received it from God through the hand the Angel Pamphilius.

It contains a series of invocations to be spoken while fixating upon a set of intricate and complex drawings (or Notae) that enable the practitioner to learn at an accelerated rate and quickly comprehend complex subjects as would one if they had an eidetic and photographic memory.

Some copies and editions of the Lemegeton omit the Ars Notoria entirely. Those that do, follow Robert Turner’s 1657 English edition, which is evidently his own translation from its first Latin appearance in Agrippa’s Opera Omnia (ca. 1600). Neither edition included the most vital component of its operation, the Notae, which in its absence, renders the entire system inoperable.

For comparison, I have included a facsimile of the earliest known manuscript of the Ars Notoria, (Yale University’s Beinecke MS Mellon 1) in the Related section. This edition is attributed to the magician Apollonius of Tyana who called it Flores aurei, or the Golden flowers, For more detail about this work, please see my full entry here.